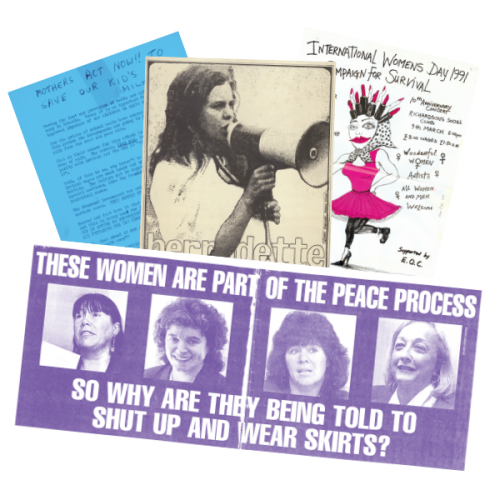

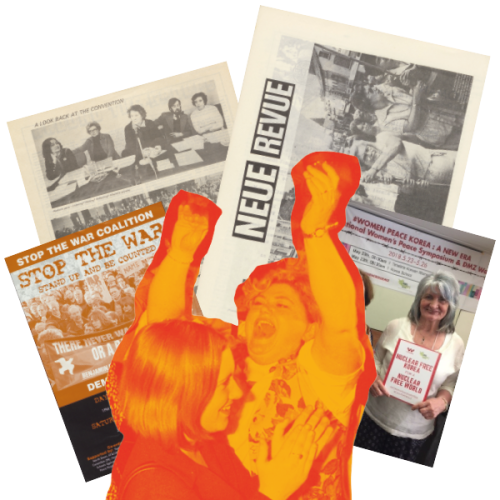

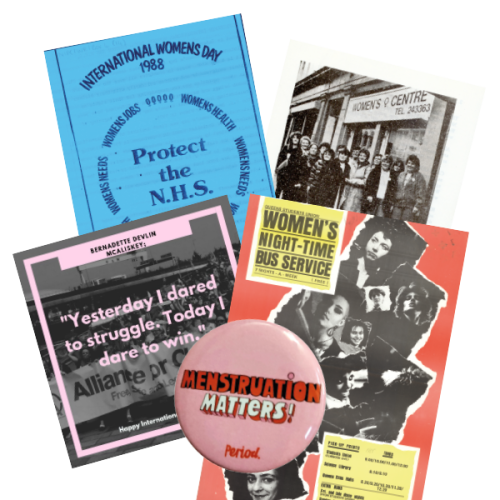

‘These are the women we need to be celebrating – the ones setting up the women’s centres.’

extraORDINARYwomen participant

In the years before 1965, education for women frequently ended at an early stage, with women often leaving formal education by their late teens. Importance was placed on domestic duties, including marriage, raising a family, and running a home. While this lifestyle was chosen by some, many women expressed feeling missed opportunities and quietly mourning the loss of educational potential.

During extraORDINARYwomen engagement, women noted that leaving education early meant many worked in physically demanding jobs such as in factories or mills. For those women a fire was lit; determining them to spur their children on to achieve goals denied to them.

‘I don’t know how she did it. She’s the eldest of eight kids, she dropped out of school to look after her siblings, and at 18 or 19 got married and started having babies of her own and ended up with five. My mum was always adamant that we would go to Uni, that all of us would go...

Coming from a working-class area that wasn’t really the done thing... a lot of people didn’t go to Uni, and my Ma really pushed us in our education and I’m grateful to her for that because growing up in a working-class housing estate, you could have easily just fell off the face of the planet.’*

While issues around accessing and remaining in education progressed, female students were still at a disadvantage when sitting assessment examinations for secondary education during the 1970/80s, with a higher pass mark set compared to that for male students, which impacted the number of female students progressing to grammar schools and exasperated limited opportunities for educational and career development.

But challenges were made to expected work roles for women, with women articulating aspirations to be scientists, engineers, lawyers, doctors, and other professions previously perceived to be reserved for men.

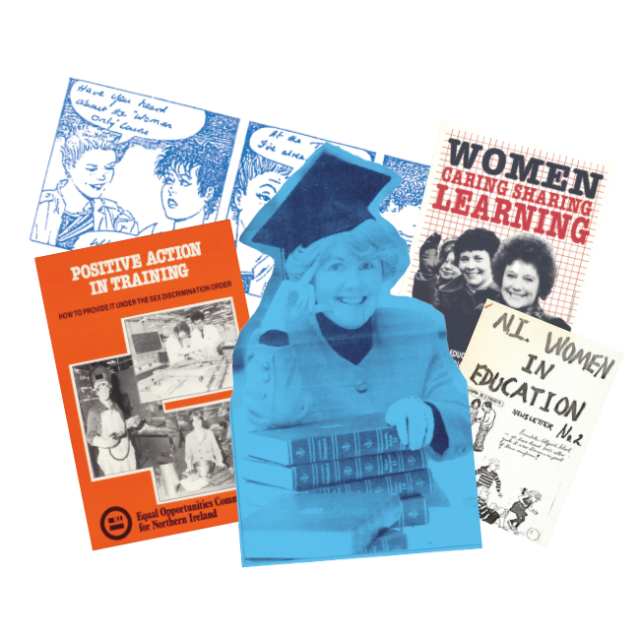

Women talked about finding confidence which, coupled with ability and opportunity, saw new pathways emerge. In the 1970s, All Children Together campaigned for integrated education. Professor Pauline Murphy founded training networks in the 1980/90s, including the Women’s Opportunities Unit at Ulster University which provided the first formal university education programme specifically for women. This was followed by the founding of organisations including Parents Action Group for Education, Unemployed Young Women’s Project, and the Ulster People’s College, benchmarking a change in attitude to women in education. Women took the reins in educational leadership, policy, and advice.

Local community and education centres promoted women’s issues via tailored workshops and classes. Many of the women we talked to during extraORDINARYwomen cited these classes and advice services as providing vital support for women who lacked qualifications.

In 1983 the Women’s Education Project was created to offer regional support infrastructure for the women’s sector. Women discussed achieving further education qualifications and progressing to study at university, acquiring specialist knowledge and skills.

*extraORDINARYwomen participant